How one fellow who had appeared to have no arguments and who had not even been sure of his point, was responsible for changing the minds of a diverse group, how the man who initially claimed he wasn’t trying to change anybody’s standpoint was exercising influential leadership. And what lessons or insights can we derive as the individuals who care?

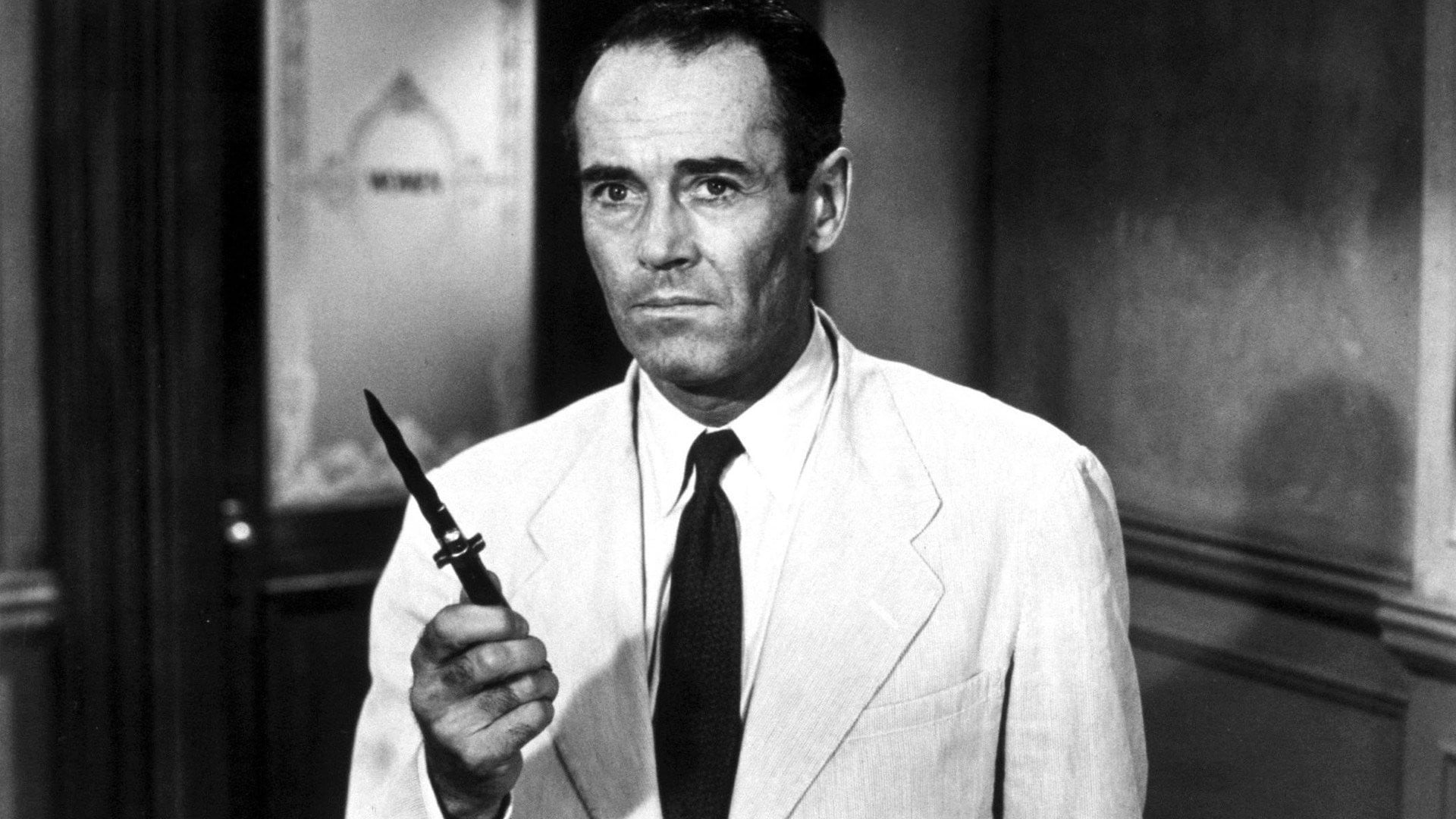

No big deal, just a group of guys, one tiny spot, an easy plot, and it’s all very much about leadership. Twelve completely random folks were obliged to decide whether a young kid is guilty or is not. Eleven of them seemed not to give a damn. If the kid were to be found guilty, they would simply have him sent to die. One guy was iffy about it. He was not against the others, just doubtful. Thanks to his uncertainty, we see a great deal of discussion, although at times a heated exchange. Theoretically, there is nothing else in this iconic movie. So why the hell is it the 6th top-rated IMDb movie of all time?! The 1957 movie, the black-and-white one titled ‘12 Angry Men.’

This article is based on the 1957 film ‘12 Angry Men,’ whose script reflects the social realities and judicial practices of that time. Back then, juries were typically all-male, and women rarely served as jurors. Over the years, this has improved, and today women are equally represented on juries in the US courts. However, this change has been gradual, has taken many years, and we owe it to the efforts of many tireless initiatives (including legislative changes, social movements, and activities aimed at raising social awareness of gender equality).

The movie ‘12 Angry Men’ serves as a guide to understanding how to act as a leader and how to debate. Haven’t seen it yet? This quite realistic portrayal of group dynamics can be a good example of real-life scenarios, more so than many academic studies and MBA programmes. It is indeed worth seeing. If you have not seen it yet, I would recommend watching it first, then reading through these notes. Therefore, now I can assume that you have watched the movie.

And just one more little disclaimer before I start. Yes, the movie can be perceived as deceptive and cynical. Yes, I have read about the emotionally manipulative ploys used and how these tactics may be misleading for the audience. As it is all very much about human beings, I don’t argue with them and assume that Juror 8’s intentions were merely honourable and trustworthy. But as it is with all human matters, you can never fully define (or justify) everything. Bear this in mind; it is also a valuable point.

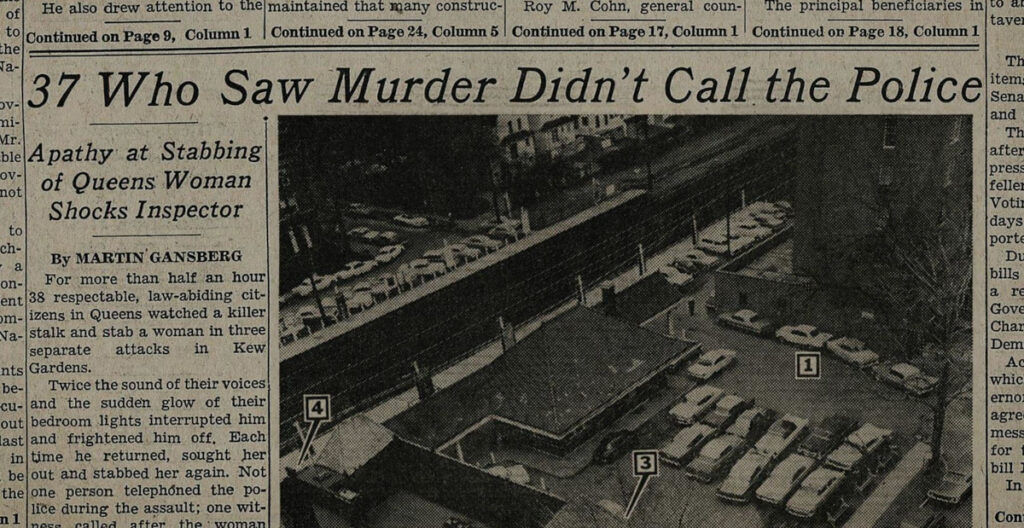

Diffusion of responsibility

Our 12 angry men were not only confronted with a new problem, as many of them were serving on a jury for the very first time. They were also fully anonymous to each other; they were even being called by their numbers rather than their real names. Here is the thing: wasn’t it just easier and more convenient not to take any action? It might not have been due to their apathy or indifference, but rather because they were strangers. The presence of other people makes a real difference when it comes to our own opinions, most commonly making it very difficult for us to stand out.

It has been proved that in the case of some unusual circumstances, the larger the group of people is, the less likely it is that someone there will take responsibility for action. This counter-intuitive approach, contrary to mathematical probability, is a tangible manifestation of the social loafing concept. Furthermore, if someone is a member of a group, it may make them feel more anonymous, thus they are more willing to act according to the group standards than their own beliefs. A not-so-fun fact is that you are almost three times less likely to receive help while lying on a crowded street than if you were seen by only one observer.

Unfortunately, we really experience that. A specific example I would like to mention is the high-profile story of Kitty Genovese. Kitty was attacked and stabbed to death outside her apartment building in Queens, New York. There were many investigations and it was established that dozens of people witnessed the assault but did not take any action (obviously, they thought others would). There was enough time, and it was as simple as picking up the phone and making a call, but they did not. This is quite an old story from the ‘60s, and it can be considered oversimplified, but it triggered and inspired many scientists to study the phenomenon in question. The case led to the introduction of the term ‘Volunteer’s Dilemma,’ which is strictly related to a common good that is only produced when at least one person volunteers to pay an arbitrary cost. Fast forward and today we have more complex consequences of the diffusion of responsibility, such as electronic driver assistance systems that require drivers to maintain attention and intervene when necessary. Studies have shown that drivers are less focused when the automatic driver assistance system is active, and their intervention is less likely.

Let’s get back to ‘12 Angry Men.’ It must have been very difficult for the Juror with number 8 (by the way, what a brilliant role played by Henry Fonda) to stand out from the group, but by making that extraordinary move, he naturally proved his strong will and firm beliefs. No matter what they are, they are extremely important in leadership. From my perspective and based on my own experience, a leader is obliged to have a coherent vision. Up until now, it might seem a cliché, but according to what we see in the movie and according to my thoughts, they do not have to be strongly convinced of their ideas. Leaders are obliged to take on responsibility rather than provide solutions. In other words, they do not have to be right, but they must believe in something that can be significant and meaningful. And truly care.

Believe in something

There were other quasi-leaders in the room. In some reviews jurors with numbers 1 and 3 are also indicated as leaders. Let’s consider the one with number 1. The Juror was the chairman of the jury by virtue of his position, which gave him a certain authority. Authority in itself does not facilitate the exercise of leadership, and may even make it more difficult. He was fulfilling his duties; he tried to maintain control over the group but being challenged by some of them he reduced everything to managing successive ballots. He acted according to the role assigned to him rather than his personal needs, and he failed miserably. Typically, this does not work, as others may perceive such people with little respect. Respect is not merely a matter of the role (note that some jurors referred to him as ‘Foreman’ simply for convenience), nor is it solely a duty. Incidentally, if you want to divide the group, then call for a vote. True leadership requires personal commitment and one’s own reasons or beliefs. Whatever you name it, there is no leadership without a cause; it cannot exist without believing in something.

Having a strong reason alone is not sufficient. Jurors number 3 was driven by his personal demons; Juror number 7 was preoccupied with his baseball tickets. Indeed, they all had their reasons to want to conclude the awkward gathering quickly. Yet, only one juror was genuinely invested in their collective role. This individual was willing to face a challenging situation, not out of self-interest, but due to a sense of responsibility towards the group’s duty. He may have gone against the grain, but this is often what true leadership looks like.

Be a decent man

That young man could have been condemned to death, and it was highly probable that he would be. Juror number 8 wasn’t certain of the kid’s innocence. It is difficult to determine whether he had a clear opinion on the matter, or whether he was ready to defend the boy by any means; nevertheless, his stance was not emotional. Juror number 8 simply wanted to do the right thing. Without prejudice and with an open, humane mind, he aimed to uphold a certain standard, perhaps that of decency.

Choosing what is right over what is easy is not a simple task, and adhering to one’s own standards is the hallmark of gifted leaders. Leadership does not align with laziness; rather, it is an endless pursuit of rationalization, righteousness, and value. Trust in yourself and be moral, without a doubt!

The second consideration is your behaviour. Opposing others is not a simple matter. How do you engage in debate rather than descend into an argument? How do you avoid personal tensions and arrive at fair conclusions? To begin with, keep personal objections to a minimum. The only permissible challenges are those against someone’s reasoning. While you can always question the reasoning, you should not challenge its authors. Never allow debates to become personal. Never make them about the person behind the reasoning. It’s extremely difficult and you won’t always succeed. As one of my professors used to say, “you never correct a mistake, you always correct a person.” Be very sensitive to this, and ensure that your objections affect others to the least possible extent.

Furthermore, maintaining coherence in the discussion and sticking to the topic at hand is crucial. This is often referred to as maintaining the ‘flow.’ It is essential to ensure that the debate remains centred on relevant points. Do not permit the introduction of disruptive or emotional topics, as these can result in going off at a tangent and distract from the issues already under consideration. Keep an eye on the main thread and steer clear of unnecessary side discussions. Defend your position and ensure that the debate stays focused on your point until it has been properly questioned, challenged, or accepted.

A game of chess

Magnus Carlsen, the current world chess champion, has said that he treats the game of chess as a battle of ideas. Everyone has their own plans and assumptions. The enjoyment comes from demonstrating the effectiveness of one’s strategies and the accuracy of one’s situational analysis.

The same principle applies to disputes. One bad decision can undermine your strategy, even if it follows a series of many good moves. Sometimes, you must sacrifice some of your advantages; other times, you cannot act too hastily. Regardless of the situation, you are solely responsible for any openings you give your opponent to defeat you. Therefore, the question arises: when and how should you confront your opponents?

First and foremost, you must choose your battles. It’s impractical to contest every single point. Be ready to make some concessions in a debate. Excessively questioning your opponent’s points can appear unwise. Ultimately, you must determine whether the confrontation is warranted.

Juror number 3 stated with certainty and conviction that one piece of evidence was credible. However, this made him completely unreliable when it turned out that the evidence was indisputably incorrect. That was certainly an all-in move and the wrong battle to choose. Even though we cannot foresee the future and can never be completely certain, it is always wiser to rely solely on cold, hard facts. These facts should be free from personal interpretation. You can develop a vision based on them and add a bit of conjecture, but remember to establish strong and undeniable foundations.

Bearing this in mind, also focus on challenging the points of others on a purely factual basis. As in a game of chess, where each player has their own moves, adhere to this rule. Prioritize being factual over interpretative as much as possible. Similarly, in chess, do not allow your opponents to overlook a fact or assert something that is not factual. Can you feel it? It is almost always worthwhile to highlight these issues. Simply remind others of the facts or state them if necessary. This approach is always impersonal and holds undisputed power in elevating the quality of the debate. Rather than your opponent, personal confrontations can often harm you more, so follow the rule and refrain from criticism.

Be factual and rational. Steer clear of personal conflicts. Adhere to the rules of your chessboard. You may lose a battle or make a poor move, but don’t give your opponent an advantage, and don’t belittle yourself. Always keep your strategy to win the battle at the forefront of your mind.

You can’t change their minds

The group of those 12 angry men had a distinct protagonist (Juror 8) and a separate antagonist (Juror 3) among them. While Juror 8 was non-aggressive, soft-spoken, and open-minded, Juror 3 was highly confrontational and very opinionated. Although Juror 8 rarely expressed outright disagreement, Juror 3 contested every single rebuttal presented to him (an awesome role played by Lee J. Cobb).

The man with number 3, who advocated for the boy’s guilt, never conceded a good point when it had been made by any other juror. On the other hand, Juror number 8 expressed a lot of sincere agreement with his opponents. So, how did he win over the jury? Well, in order for someone else’s mind to change, they must believe that your mind can change.

Adhering solely to your own presumptions, regardless of the facts, is always an unreliable and even discreditable approach to deliberation. Contesting a reasonable point is itself unreasonable. Therefore, demonstrating that your mind can change is essential for helping others to reconsider their views, and this can only be achieved by being open to different perspectives. If your opponents think you’re not open to changing your mind, they won’t be open to changing theirs. You can’t change their minds. You can’t change anyone else’s mind. Only they can.

Again, it’s more beneficial to agree with a good point than to remain merely an opponent. Certainly, you will lose some battles on your way to winning a war, as Juror 8 did. However, what was most important to him was maintaining his credibility and integrity, which he did throughout the entire debate by avoiding the unreasonable and emotional opinions that other jurors were so fond of.

Integrity

Not much is known about the jurors at the beginning of the movie. As the plot develops, however, the nature of each character is revealed to the audience. Their origins and social positions are different, but what also distinguishes them is their integrity. The concept of integrity emerges in the example of Jurors number 3, 4, and 8. Juror number 8 appears as an example of honesty and uprightness, showing compassion and not allowing irrelevant factors to influence his judgment, while Juror 4 maintains his integrity by ensuring a fair trial for the boy by adhering to the principles expected of him. Although Juror 4 does not show concern or compassion, he votes based on the facts and evidence alone. Juror number 3 naturally allows his personal problems and biases to influence his convenient assessment of the facts, he is personally prejudiced and often fairly unpleasant.

Integrity is fundamental. Although it may not be sufficient on its own, it remains crucial. Let me mention the Foreman who does show integrity when confronting Juror 10 over his rudeness: “You want to do it? Here. You sit here. You take the responsibility.” And then, when Juror 12 typically says, “The whole thing’s unimportant,” he replies, “Unimportant? You want to try it?” indicating that he takes the role seriously. Such tiny reactions have profound implications on how other people perceive us and trust us.

Certainly, this is not the sole action to take as a leader, but it is definitely a crucial one to maintain your integrity. You can be wrong, you can make bad decisions, but you should never persist in your mistakes. Be frank, be honest, and listen to your opponents. Apologize when you make a mistake and focus on others, rather than on yourself.

Leaders with integrity set the tone for a holding work environment. Their commitment to ethical behaviour encourages a culture where accountability and honesty are valued, leading to a more positive and productive workplace. Integrity is the foundation of trust. When group members and leaders consistently act with honesty and moral principles, they earn the trust of their colleagues and stakeholders.

Work avoidance

The concept of work avoidance is illustrated through the jurors’ reluctance to engage in the difficult task of thorough deliberation. This behaviour mirrors what often happens in group settings, where some members may seek a quick resolution to avoid the discomfort of deep analysis and conflict.

The film showcases how certain jurors are more interested in reaching a hasty verdict than in ensuring justice, which is a clear sign of avoiding the hard work of critical thinking and moral reasoning.

There is a juror who is in a hurry because of the baseball game tickets in his pocket, another one feels hot, and yet another gets involved in conflicts on a personal level. The Foreman’s role becomes crucial as he navigates the group through these challenges, moving from initial conflicts to a stage where each juror’s input is taken seriously, and the group works together towards a common goal. However, the first one who invites the others to diligent work is Juror 8 who says, “it’s not easy for me to raise my hand and send a boy off to die without talking about it first.”

Based on my personal experience, I can assert that conflict and polarization can easily turn into work avoidance. This effect is further amplified by mechanisms of social loafing, where individual effort diminishes as group size increases, leading to a lack of accountability and reduced motivation to participate actively in the group’s task. To mitigate the effect, the Foreman’s leadership is key in steering the group through the norming and performing stages, fostering a culture of collective efficacy where each juror’s contribution is valued, and the group works cohesively. This is particularly challenging when the work to be done is of an adaptive nature, meaning the problem we are facing is not fully recognised or well-defined.

Following general work avoidance methods, neutralisation techniques often unfold concurrently. Neutralisation occurs when jurors, seeking an escape from their own internal struggles, neutralise them by attempting to present the facts in a different, often seemingly logical, light. A common example of neutralisation is observed in prisons where inmates, when asked about the reasons for their incarceration, typically list a series of rationalisations that portray the crimes they committed as relatively justified. The jurors in ‘12 Angry Men’ are a diverse group of individuals, each with their own unique backgrounds contributing to the deliberation process. Although initially we know little about them, we quickly learn a bit about their personal stories. This context is often used to attempt to neutralise each other’s views. Marginalisation of opposing arguments is expressed when Juror 10 tries to oversimplify by saying, “He’s a common ignorant slob.” There are personal attacks, attempts at division, and even seduction, as when Juror 7 says, “Let’s break it up and go home.”

Amidst this backdrop of diverse perspectives and the ensuing conflict, Juror 8 emerges as a pivotal figure, steering the group back to their collective duty. Juror 8’s references to the jury’s purpose and their individual responsibilities are the concrete examples of how effective leadership and a commitment to the group’s purpose can help overcome tendencies to shirk responsibilities, ensuring that decisions are made with careful consideration and integrity.

Groupthink and shift

We tend to overestimate the power of meetings. I am sure you have participated in many where people discussed a matter using different standpoints, perspectives, or drew wise arguments. Even though meetings are mostly frustrating, time-consuming, and simply exhausting, wouldn’t you agree they can yield the best results possible? We subconsciously believe that by considering different opinions and experiences, we create more balanced statements, but it is not so obvious. However counter-intuitive it may seem, in most cases, it works differently. Social acceptance, conformity, and cohesiveness are our innate traits. Human beings are often very averse to acting contrary to the trend of a group, which results in the fear of the group’s potentially negative attitudes towards them if they go their own way. While we think in our own way, we do not want our thoughts to be disclosed and exposed to the group. Psychological studies have addressed this, formulating two phenomena: ‘groupthink’ and ‘groupshift’ (both closely related).

We naturally reckon that the accumulation of knowledge and experience supports us in finding the best possible solutions or making decisions. We believe that versatile collectives and comprehensive analyses help. I do think so, but they all need a thoughtful approach.

It comes as a surprise that when people care about loyalty to the group and want to minimize conflicts, the group’s capability – let’s call it ‘group intelligence’ – is not greater than the intelligence of their individual members. That being said, some committees’ decisions or collective arrangements are often worse and would be better if they were made by individuals. The group is prone to the illusion of their intellectual superiority and infallibility. The higher the social status of group the members, the more likely this is to occur. People are just afraid that their standpoints are against some sense of togetherness and consequently self-censor their own discourses, thus limiting their own intellectual abilities. There are more factors that make group decisions so vulnerable, but this one should give food for thought. The ‘groupthink’ phenomenon has not been studied extensively yet, but it is thought to be a reason for the U.S. Navy and Army’s defeat in Pearl Harbor or the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, just to give you an example of its possible magnitude.

On the other hand, group affiliation may also radicalize the initial views of its members. It seems that there is a tendency for groups to take riskier positions than individuals within these groups would have taken if they had faced the same issue alone. Psychologists have coined a specific term for this, which is ‘groupshift.’ According to their studies, the difference in people’s decisions is consistent and comprehensible. Risk-averse group members tend to make even more risk-averse decisions if the group members’ opinions are risk-averse on average. Conversely, if they are naturally more risk-seeking and the group members’ opinions are risk-seeking on average, then they tend to take even greater risks. Also, the subconscious conviction that the responsibility of the group is shared makes people exhibit a preference towards riskier solutions, but this refers directly to the diffusion of responsibility I pointed out earlier.

In ‘12 Angry Men,’ we see that group discussion tends to exaggerate the initial positions of the jurors at the beginning of their session. I can say that some of them must have been at least sceptical of the boy’s guilt, but for the sake of the group’s consistency, they just went along with the majority trend. Had it not been for Juror number 8, they would have probably condemned the boy to death without giving it much thought.

Altogether, this assigns great importance to Juror 8’s individual position against the group, and it’s actually an example of proactive behaviours every leader should exhibit to avoid ‘groupthink’ and ‘groupshift.’ Everyone exercising leadership should mediate, showing that not only can their own standpoint be changed, but also that they are unprejudiced, even-handed, and deliberate in considering every argument raised. The group must believe that their leader’s mind can change. Be careful when making biased summaries. Watch out for hierarchical constraints that could make it difficult for others to express themselves. Choose a person to be the devil’s advocate and routinely ask everyone for their individual doubts. Do not push them to agree at all costs.

Teamwork

Although I compared debates to a chess competition, there are usually additional collaborative traits that may be relevant to your broader leadership success. You should look for supporters as soon as possible and build a cohesive team.

It is sincerely reasonable to treat others as opponents rather than rivals. Only by doing this can you avoid ego clashes, which are often explosive and costly. Then, to demonstrate your open-mindedness, give them the subconscious feeling that they can get along with you. Show others that you are reasonable, offering them the comfort of being honest and open as well.

Being emotional like Juror 3 usually leads to inconsistency. Do not let emotions control your actions. Even when the game is on, you do not have to be its active participant constantly. You can stand beside the chessboard and observe the moves others make. You can be on the dance floor, but also step out onto the balcony and broaden your perspective.

The next step is about goodwill. There is probably nothing more important than your sincere goodwill. Goodwill is fundamental to establishing cooperation with your former competitors. You all can have different opinions, but try to avoid inevitable confrontations as long as possible. This will allow you to get to know the opinions of others and their personalities. Let them talk. Listen to them. We do like to be listened to and understood. We do not like to be ignored or underestimated. Thanks to that, you will be perceived better, and you will have a much better view of your opponents.

Essentially, you cannot force others to join you, but you can always show them that they are welcome to do so. Sometimes, when the matter is controversial and your opinion is unpopular, you may need to allow them to join you confidentially. That’s what helped Juror 8 win over Juror 9. Please remember, if someone has initially disagreed with you, it is always difficult for them to switch sides. However, you should respect and support them. Keep in mind the mutual respect between your allies in a debate. You don’t exploit them; you support them.

I’ve just said that you can’t force others to join you. You can’t, but you can encourage them by showing that they actually may not want to stay with those on their own side any longer.

Stay thoughtful

There isn’t just one reason why people are willing to change their minds; there are many. Ultimately, however, it all comes down to one thing – we disagree with ourselves. Yes. We change our minds basically because we disagree with ourselves. It’s a costly process. When a person changes their mind, what is implied is that they were wrong, not smart enough, they don’t really know what they think. We are then vulnerable; our self-trust is exposed. Our mind is the sole tool for understanding our surroundings. When it errs, correcting it isn’t just about one conclusion – it can cascade, challenging many beliefs. Questioning too much at once, we risk undermining our identity, a potentially painful process. No one can really afford to change their mind frequently, otherwise, they wouldn’t have a lot of credibility. That’s why it is so important to create circumstances that will help embrace the change.

If your opponent says something reasonable and you can test it, you are going to make yourself appear unreasonable. It’s better just to concede to a good point. Sure, it won’t look like you are winning people over at that particular moment, but you will still seem reasonable, and you’ll still appear to have an open mind, which, as we’ve already covered, will likely keep your opponent’s mind open as well. Juror number 8 rarely, if ever, expressed his disagreement with another juror. If stating your disagreement serves no meaningful purpose, don’t do that.

Juror number 3 does not see any value in this type of restraint to him if anybody reaches a different conclusion than the one he has, then that person must be confronted. This doesn’t work. Not just that it doesn’t change the mind of the person that is being confronted, it doesn’t change the mind of anybody who’s listening either. Juror number 3 hardly ever admits his agreement with others, which stands in stark contrast with Juror number 8, who regularly acknowledges his agreement with his opponents. Juror 8 passively concedes.

Listen to people, truly and with full engagement. With devotion and concentration. Actively. Such mindfulness is extremely important. When people face a conflict that occurs within them, they won’t tell you about it, but chances are you’ll notice the signs. How can you help them in the process? There are certain incentives that make it easier for us to change our minds. Being honest triggers a feeling of satisfaction and self-respect. There is some courage within yourself that may be discovered. When people are truly guided by reasonable motives and, when people see this and open their minds, they make the process easier for others, and become our natural allies.

Consensus

True leadership emerges in the presence of adaptive challenges. There is no need for exercising leadership when the coffee machine is out of order. Then what is needed is a coffee machine technician, nothing more than technical expertise. However, when we are confronted with a challenge that is not strictly defined, we are dealing with an adaptive problem. Essentially, we don’t know what we don’t know. Every day, I see how difficult it is for us to accept that some problems may not have a ultimate solution, and the best we can do is to contribute to progress. We can still steer matters in a valuable direction and aid in improving the situation, particularly when no single path is distinctly right.

We cannot change the cards we are dealt, just how we play the hand. Was the kid guilty? Was the kid innocent? We don’t know. However, it was Juror 8 who took the effort, maintained his integrity, and offered him a fair consideration of the case. If that’s not about leadership, what is? There is a significant difference between compromise and consensus. It lies in the fact that instead of clashing opposing views, we collaborate. Together, we develop a position that is common to all group members. This does not happen through concessions or quid pro quo bargaining, but by means of building good relations between the group members, which enable the achievement of universal agreement.

Take care of this polarized world. Influence people without putting pressure on them, contest without arguing, dispute without fighting. Build bridges, take responsibility, and don’t think too much you will ultimately fix the world. You won’t. But you can help it advance; you can make it a truly better place. And that is what exercising leadership is all about.